We live in a “post-secret” world. There is a sense, especially with social media, that everyone shares everything. The truth, however, is more elusive. We share what we want to share, presenting highly-curated versions of ourselves and our lives to our wide-circles of “friends”.

Never in human history have we known both so much and so little about so many people.

And it seems like the secrets we do keep are either the most personal or the most banal. We kick the mess out of the way when we snap pics of our kids, curate the bookshelves when we hop on yet another Zoom call, and let our food get cold while we find the elusive perfect lighting or angle for that “what I had for dinner” photo. We mark the milestones of life like the birthdays, the babies, and the new homes, but we paper over the disasters, failures, and disappointments. It’s somehow authentic and disingenuous at the same time.

A few weeks ago I wrote about the importance of community cookbooks: those often overlooked collections of recipes compiled in churches, schools, workplaces, and community groups. I wrote about why these books are important and how to find a book that speaks to you – to your interests, your community, your heritage, and even your aspirations.

But a comment on that post from fellow Substack writer Leigh at As We Eat Journal got me thinking:

These recipes were points of pride and a way for the submitted to have their voice heard.

That comment has stuck in my head for a while now. And with March being Women’s History Month and a war in a part of the world that hits rather close to home I have been thinking a lot about the role of women as not only as caregivers but as caretakers of culture and tradition, and how that work has evolved in the last century. Sharing recipes and cooking together has been part of “women’s work” since time immemorial. But in a world where the sphere of female influence has extended well outside the home, how has that work changed, and how have women’s attitudes changed?

And, somehow, this got me thinking about secret recipes.

I get a lot of enjoyment from sharing recipes and cooking secrets with other people. In fact, it’s the raison d'être of this newsletter: sharing the tips and tricks I learned in cooking school, in kitchens, and through a whole lot of practice. Much of what I share isn’t exactly top secret: it’s technique and method more than anything, and classic stuff at that. I don’t feel possessive about it at all: I want you to try things, share with your family and friends, and make them your own.

But if I transported myself back a hundred years, or even fifty years, a different feeling emerges.

In a world where women’s influence was more limited to home and community, recipes would have a different value. Recipes and the forums for sharing them would be some of the few places where a woman could contribute and have recognition in her own right. A church cookbook might be one of the few places a woman could see her name in print, ever. A community picnic could be one of the few places her work could be seen in direct contrast to her neighbours’. To share her best work would be a point of pride and a sign of her skill and care for her family.

But if you gave away all your secrets, what would make you special? Who would remember you?

The more of your identity is tied up in one thing the more possessive of it you will be. If much of your public persona is that you make the best pie you probably don’t want to share your exact method with anyone. In a sea of other pie bakers your excellence makes you special. There’s incentive to keep a few details secret - those details are social currency and a source of recognition and prestige.

But there’s a problem. Secrets don’t make a legacy.

I browse cooking forums and sift through food blog comments all the time. It’s heart-breaking to see the number of laments from the children and grandchildren of incredible cooks and bakers seeking, often desperately, help to recreate a dish, or a cake, or another childhood memory. They sometimes don’t know what the dish is called or only have a vague translation or transliteration from a dying dialect. Often they have made repeated attempts to get the recipe right, but something is missing - that special something that their relative did to made a dish unique. The secrets went to the grave.

And even more heart-breaking is that in a generation or two no one will remember. Your children and grandchildren will remember that “no one makes it as good as Grandma did”, but your great-great-grandchildren? They won’t know a thing about it.

So while today, in our modern world, our identities are less directly bound up in the domesticity of hearth and home, we feel less possessive about our secret recipes - our diversity of interests, opportunities, and cultural influences almost ensures it.

What to do then? How can you preserve the truly special recipes in an overwhelming ocean of information over-sharing?

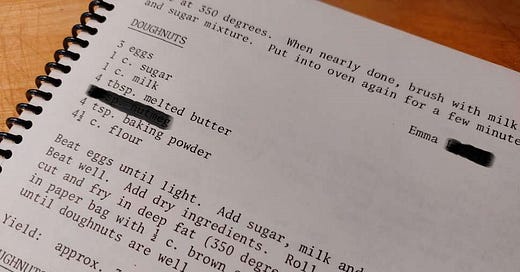

If a recipe is special to you and your family, write it down. Pin down the aunts and uncles, grandparents, siblings and cousins for their favourites. You might be surprised at which meals trigger nostalgia. If written recipes exist ensure that they are copied along with notes, modifications, and the scribble in the margins.

If the owner or keeper of the recipe is alive, make time to cook with them. Watch them make it, and make it with them. Let them watch you make it. This is especially important if you consider yourself a good cook - the recipe’s owner may do things that are counter-intuitive to the way things “should” be done. Measure the previously undocumented pinches and and drizzles. Many excellent cooks resist sharing recipes because of the bother of writing them down, so do it for them. How many grams of lard is in the “lump the size of half an egg”? What size can of peaches? How much garlic is really in that sauce? You’ll never truly know until you see it done. Document everything in detail, make no assumptions, and resist the urge to “fix” anything.

Teach and share. Make the recipes with your family and give copies to anyone who asks. If you’re not publishing a cookbook or bottling a sauce your recipes don’t have a commercial value, so there is no reason not to share them as widely as you can. The more hands making loaves the less chance the recipes will be lost. Spread the joy of pot roast and pie crust as you would good news.

Most importantly though, give them a name. Write down your aunt’s Christmas cake recipe and and make sure that that her name is attached. It’s not “Family Christmas Cake”, it’s “Charlotte Smith’s Christmas Cake.” I’m betting she will gladly tell you how she got the recipe, when she learned to make it, that it’s really better the second year, and that she’s always cut back on the cloves a bit in exchange for the pride of her name attached.

So while we may not be so driven to keep secrets as in the past, we are still driven by our need for connection, ownership, recognition, and identity. When you think about it those are the real secret ingredients.

When I receive a recipe from someone and add it to my personal recipe book, I always add the person's name along with the date they gave it to me. Looking back at recipes that girlfriends gave me 30 years ago often reminds me of the time when I first tasted that food and the event surrounding it. Memories!

My brother in law has his mother's recipe book, hand written in Italian. She started it in Italy when she was 13. Recipes from her mother and grandmother. I've been bugging him for years to get it translated!