“It’s easy when you know how it’s done” goes the early aughts pop anthem (and advertising darling) Jerk It Out by Swedish group The Caesars. I remember it as the song that sold me and my Gex X friends their first iPods, a device that was as revolutionary as its white headphones were ubiquitous. The iPod legacy is still with us every day, long since blended into the devices most of us carry that serve as everything from health trackers, calculators, meditation coaches and occasionally even as phones.

Apple had introduced us some years earlier to bright candy-coloured computers and their iPods were no exception: they made computer shit actually kind of fun and a little less intimidating for those of us who weren’t born digital.

But “it’s easy when you know how it’s done” applies to cooking, not just computers.

Candy-making scares off a lot of people. It’s seems complicated, likely involves a pile of odd ingredients (as the back of a bag of sour gummies will attest) and seems a bit unnecessary since the dollar store or the nearest checkout aisle can easily provide us with our fix. For the somewhat initiated candy-making involves some rather intimidating directions like very specific temperatures and terms like “thread” and “soft ball” that seem to have dire consequences for violation. It’s enough to put off the most confident of cooks.

We’re adults, and adults don’t like to fail. Even when we’re talking about candy.

But, thankfully, there is a very simple way to introduce yourself to the art of candy-making that does not involve any weird ingredients and even a special candy thermometer is optional. You probably have all the stuff you need right in your pantry and fridge.

Tanghulu is a traditional form of candy-making common in Northern China. Imagine fruit on a stick, coated in a crunchy candy shell and you’ve got the idea. In China one of the most common fruits used the haw berry, but nearly any fruit will do.

Now, I haven’t been China (yet!) and can’t speak from personal experience about its street food culture, but I do know a pretty standard cooking technique when I see one. Cooking a 2:1 mixture of sugar and water to 300F creates what is know as “hard crack” candy - the rock-like stuff we know best from holiday candy canes and sketchy doctor’s office lollipops.

300F is the point when the water in a boiling sugary syrup has evaporated and in only a few more degrees begins the wild ride from golden amber to burnt and ruined. But modern technology (a good deal older than the iPod, that is) can keep track of this for us and there is a very simple old-school trick to check your work.

For this reason, tanghulu is an excellent introduction to candy-making. There’s little investment in pricy ingredients like butter and cream, and if you can white-knuckle the “hard crack” stage you have something rather impressive. I’ve said before that the simpler the technique the more important the details, and in this recipe you focus on one thing - the temperature of the syrup.

I will, in the interests of everyone’s well-being, mention that this is a great recipe for children, but should not be made with children, under any circumstances. Pets should equally be banished from the vicinity, and all precautions you would take for deep frying should be taken, and perhaps doubly so. Hot sugar not only burns, but it sticks and burns, rendering it’s destructiveness similar to napalm. You have been warned.

You’re an adult though. You can do this. Trust me.

The Gear:

Cutting board

Knife

Small pot

Measuring cups

Bamboo skewers

Sheet pan

Silicone baking mat or parchment paper

Candy/deep fry thermometer (optional, but recommended)

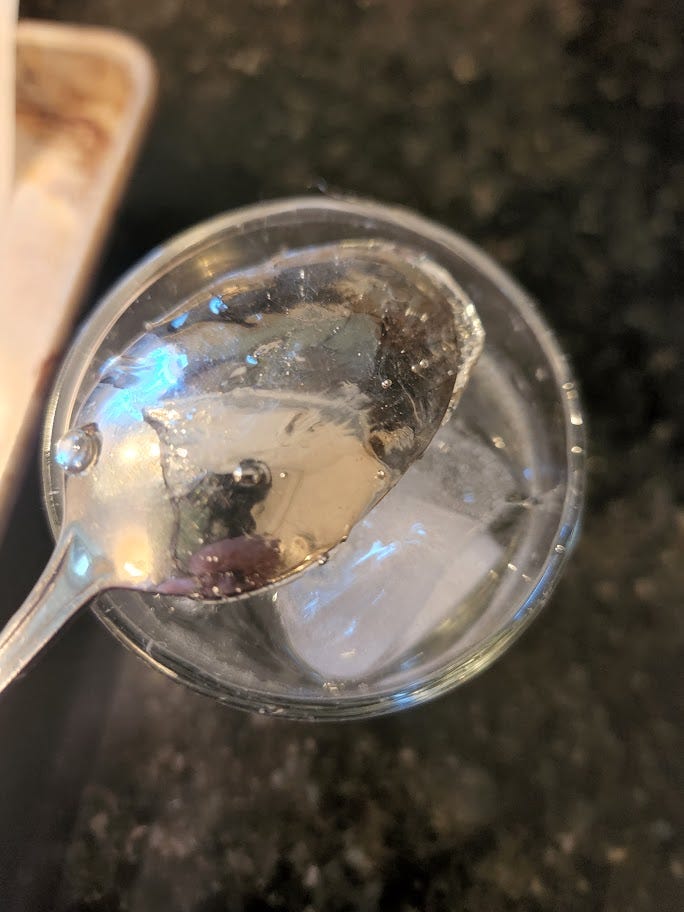

Glass of ice water

Metal teaspoon

The Ingredients:

Assorted fresh fruit (strawberries, grapes, blueberries, cherries on stems, cut nectarines, peaches, pineapple, etc.)

1 cup white sugar

1/2 cup water

cooking spray (optional, but recommended)

The Technique:

Line baking sheet with parchment paper or baking mat. If you’re using cheap parchment (the stuff you get at the dollar store) lightly spray the paper with cooking spray.

Slice/trim your fruit and impale on bamboo skewers. You want 1 to 3 pieces per skewer.

Bring the 1 cup of sugar and the 1/2 cup of water to a boil in your pot.

Attach candy/deep fry thermometer to your pot. Mine refused to attach so I checked it now and then. If you don’t have a thermometer keep your glass of ice water and spoon close by.

Bring the boiling syrup to 300 F. Depending on the size of your pot this will take 5-10 minutes.

When the syrup starts to thicken, dip your spoon into the cold water, then into the syrup. If it hardens instantly, you’re at the right temperature. If not, check again in a few seconds. This is pretty darn close.

Once your syrup has reached 300F and/or it hardens on the spoon remove the pot from the heat. A few more degrees and you’re risking it burning, so no messing around here.

Tilt the pot and dip/roll each skewer in the syrup. I don’t have any photos of this part since I banished helpers from the kitchen. Try to cover the fruit completely with syrup. Cherries can be dipped while holding the stem - carefully please!

Place skewers on baking mat/parchment sheet. Do not hold them upright lest you drip sugar napalm on your hands.

Once cool, consume with reckless abandon! You’ve made candy!

While you can cover your skewers in plastic wrap and keep in the fridge for a few days, tanghulu are best consumed as soon as the burn risk has subsided. They will get weepy and sticky at room temperature, so be somewhat decisive in your planning. They may drip a little juice from the bottom if you’ve missed a spot, but a bit of messiness is part of the fun. They look pretty cool and make even fairly unremarkable fruit taste great.

And if you screw it up? Calibrate your thermometer by testing it in a pot of boiling water (they can be off by as much as 10 degrees!) and try again. Didn’t cook your syrup long enough? Your skewers will still be delicious, but a bit on the sticky side. So what? You’ll get it next time.

And that’s the cool thing, right? You’ve made candy, and all those scary recipes with temperatures and fancy terms aren’t all that scary any more, are they? And unlike your first iPod or the latest gadget, no one is asking you to replace your vinyl and cassettes with something new - you’re adding a new trick your cooking playlist.

It’s easy when you know how it’s done.