Leave it to Le Cordon Bleu to make a cuddly toy named after a sauce.

This little guy is called Béchamel Bear. But try to convince any budding culinary student that sauces can be fuzzy and cuddly and you’ll get a dead stare with an eyeball twitch.

In French cuisine sauces are serious business.

Auguste Ecoffier, many many moons ago, helped to codify the basics of French cuisine. This codification is one of the great strengths of French cooking: if everyone has a firm grasp of the techniques, ratios, and rules around the essentials the Chef has a shorthand for getting things done and the true artistry can shine through. One of those important codifications are the five mother sauces: béchamel, velouté, espagnole, hollandaise, and tomate.

And knowing how to make these sauces opens up the whole world of French cuisine because almost every other sauce is a derivative of one of these. A reduced sauce espagnole is a demi-glace. A velouté + reduced cream is a Sauce Suprême. Hollandaise folded with whipped cream give you a Sauce Chantilly. Espagnole with shallot and mushrooms? Sauce Chasseur! The list keeps going and going…..

But even basic structures are still made from blocks. And the basic block of three of the five, béchamel, velouté, and espagnole, is the roux.

A roux is a liaison, a cheffy term for a thickening agent. It’s by no means the only one: the list includes things like egg yolks, starch, and more esoteric choices like blood and seafood coral (think lobster guts). Liaisons bring the components of a sauce together making them, well, saucy.

So knowing how to make a roux is pretty basic, like cooking school 101 type basic. And as I have mentioned before the simpler the preparation, the more important the details.

What is a roux, exactly?

A roux is a combination of fat and flour (equal parts by weight) cooked together. The fat coats the flour particles, allowing them to disperse through your liquid of choice (usually milk or a stock) without clumping into pasty blobs. Cooking the mixture eliminates the dusty, uncooked flour taste. Too much fat in your roux? Broken sauce, oily slick. Too much flour? Sticky, lumpy mess. Not cooked? Sauce tastes doughy.

How much roux to how much liquid? The basic ratio is 100 grams of roux will thicken 1 litre of liquid. Once you know this you can scale up or down as needed.

See? It may not be cuddly, but it isn’t difficult. Want to try it out? Let’s make some béchamel!

You’ll need some butter (about 25g or 1 ¾ tablespoons), some flour (25 grams or about 3 tablespoons + 1 teaspoon), a pot, a spoon (preferably wooden), a whisk, and 2 cups/500ml milk. Salt and pepper are to taste.

(If you want to use a non-dairy alt-milk or vegan butter sub, go right ahead. Just skip anything with added sugar or fun flavourings like vanilla. That would be gross.)

Heat your pot over medium-high and get the butter melting.

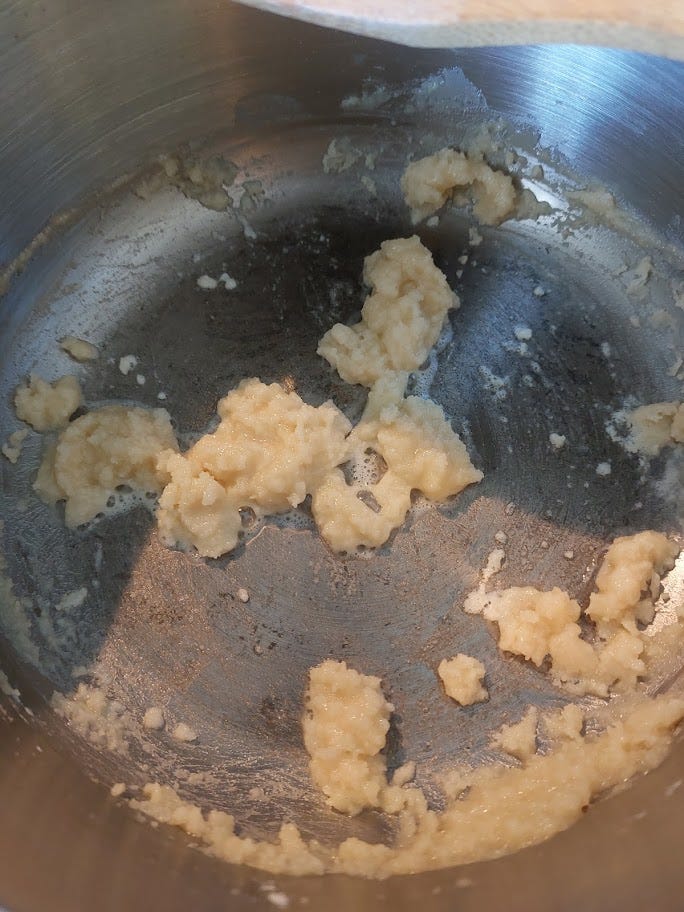

Stir in the flour once the butter is completely melted.

Cook and stir the pasty mixture until it smells like fresh baked cookies and a bit of white foam appears.

Pour your cold milk into the hot pan and start whisking until any lumps disappear (but you really won’t have any.) If you get a few lumps you aren’t a failure - just strain your sauce at the end and carry on.

Cook at medium high heat until it coats the back of your spoon. If you draw a line with your finger though the sauce and it doesn’t drip it is done.

This is not done (love my beat-up spatula, eh?):

This is done.

You can add a few chunks of onion, a little nutmeg, a bay leaf, a branch of thyme, etc. to your cooking sauce (straining after, of course) to make it a true béchamel, but you do you. I added a few handfuls of grated cheddar, some mustard powder, and a little smoked paprika to make a sauce for mac and cheese. My seven year old was pleased.

If you aren’t going to use your sauce right away you can gently press some plastic wrap against the surface to keep it from forming a skin, or you can take a piece of cold butter on a fork and gently rub it over the surface of the sauce. More butter!

A béchamel sauce can be layered into a lasagna or other pasta dish and be the basis for a gratin of anything you can find in the fridge. Its versatility is pretty darned endless.

And here’s a serious pro-level tip. You can make and FREEZE roux. Make a large-ish batch, cool it, portion it into little blocks and keep them in the freezer. Whenever you want a sauce you can whisk a frozen chunk directly into a HOT liquid. When we made the sauce above we added cold milk to hot roux. Either way we do it, we take advantage of thermal shock to make the sauce thicken faster without revving the heat. If you fire the heat too high you risk scorching the sauce. Burnt béchamel sauce tastes absolutely terrible, is a nightmare to scrub out of the pan, and stinks like a tire fire if it’s really far gone.

Once you’re confident in your roux the entire world of French sauces opens up. And once you know what you’re doing you can relax a little on the measuring too – you’ll know what YOUR sauce should look like and how YOU want it to taste. You can focus on your flavours and your flair – the science will take care of itself.

Never knew you could freeze a roux. Handy to have in a pinch

Good article simple but effective